"Pulitzer Prize ... behind bars"

For nearly as long as there have been newspapers in America, there has been a prison press.

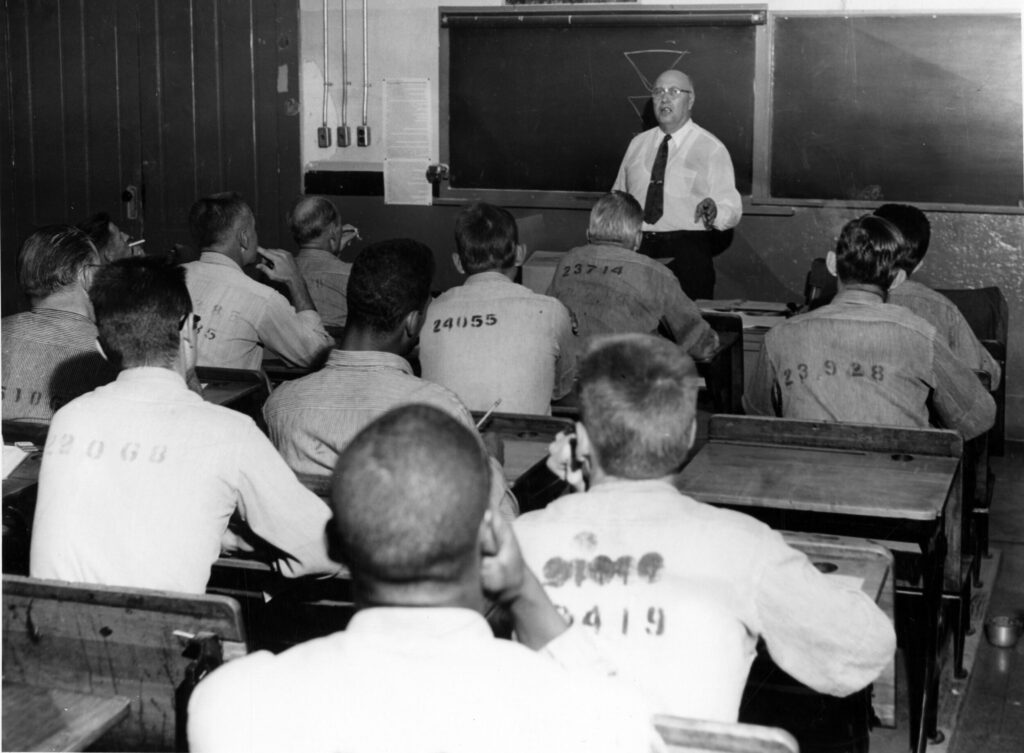

The Forlorn Hope appeared in 1800, a tiny paper that an impoverished lawyer named William Keteltas hoped might free him from New York debtor’s prison. By 1887, ambitions grew when a group of bank-robbing brothers founded The Prison Mirror at Minnesota State Prison. It became the first publication in the U.S. managed exclusively by prisoners. Their stories of life behind bars attracted a wide outside readership, including daily newspaper editors in Minneapolis and Chicago. By the late 1930s, nearly every major U.S. prison had some form of prisoner-produced publication, which editors used to champion free expression and initiate change.

Despite the mid-century “harelike growth”, as historian James McGrath Morris called it, prison publications struggled historically to connect with a broad outside audience. Author James Fixx made this point explicitly in a 1963 article for the Saturday Review.

“This corner of the fourth estate is largely unknown to the very audience it is most anxious to reach, “ Fixx observed, “the ordinary person with a reasonable concern for the problems of his society.”

Besides the occasional profile of a prison publication in an outside publication, not much had been attempted to amplify the press behind the walls. That is, until Charles C. Clayton had the vision for a contest.

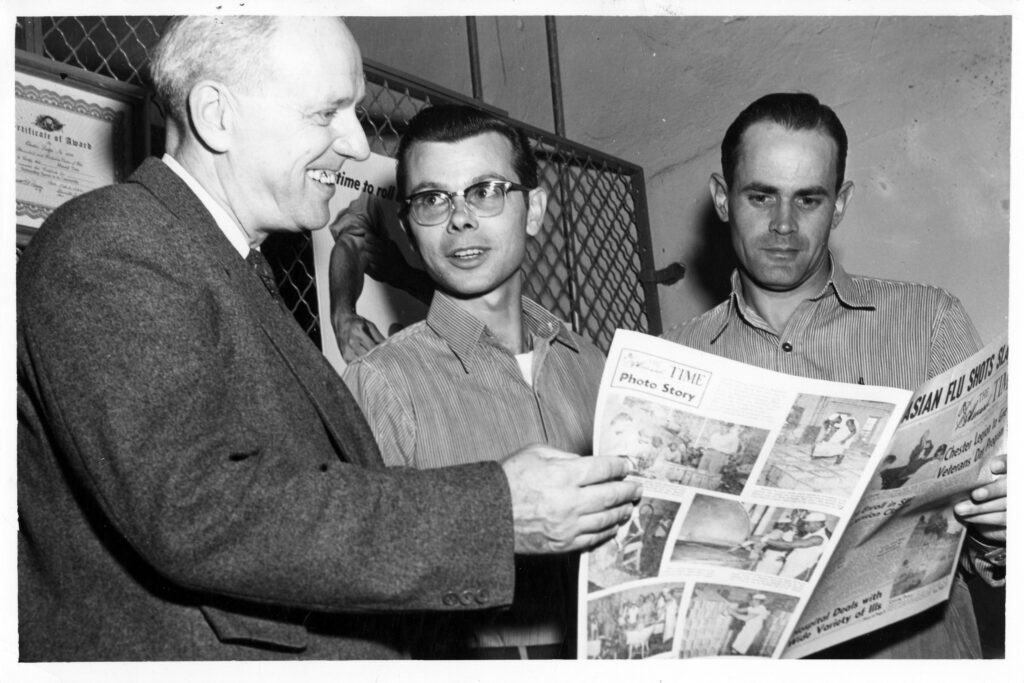

Clayton was a journalism professor at Southern Illinois University, Carbondale (SIU) and a long-time advisor to Menard State Prison’s long-running newspaper, Menard Time. With the support of his department, he launched the American Penal Press Contest, in 1965. Announced in The New York Times, among others, the initial competition included many individual story awards as well as a sweepstakes for best newspaper, magazine, and mimeographed publication.

Professor Manion Rice, award coordinator from 1967 to 1988, recruited judges from the journalism faculty at SIU and universities in neighboring states, from local high school and community college instructors, from local newspaper staff. By the time Clayton retired, in 1971, submissions had increased from several hundred to over 1,000.

Over time, as Pollen Editorial Director Kate McQueen wrote, the contest became a way to “scale serious feedback, and to build a sense of common ground with the industry outside.”

But a growing emphasis on law-and-order policies and rising prison populations in the 1980s meant a reduction in funding, and tolerance, for prison newspapers. Prison newspapers stalled all around the country, and with them, the contest. The American Penal Press Contest dwindled until SIU could no longer keep up its management. The program shuttered in1990. By the time McGrath Morris’ history Jailhouse Journalism was published in 1997, only one of the frequent award-winning prison publications was still in print.

Twenty-five years later, the prison newspaper landscape is slowly repopulating. The time is right for the American Penal Press Contest to spring back into its supporting role. It’s with this enthusiasm that Pollen Initiative and SIU, with the help of advisors and judges, shepherd this relaunch into the 21st century.